ARTICLE:

A plea for a Simple Solution: What a Performative Theory of Illo-cutions Really Looks Like

Peter Widell Aarhus University

1. The aim of this paper

In this paper I will present a criticism of the classical speech act theory (Austin 1962; Searle 1965, 1969). In contrast to this theory which operates with four to five types of basic illocutionary acts (Austin 1962, lecture XI; Searle 1975), I will argue for just one type: the assertive. Assertives are speech acts which can make locutions (propositions) true or false. It is my major argument that the assertive is the only kind of illocution we need, and that any suggestion that it should be otherwise has bad consequences for ontology, logic and a decent theory of meaning.

Since the performative analysis, the tripartite distinction between locutions, illocutions and perlocutions and the basic taxonomy of illocutions, especially Searle’s, is going to play a major role in my considerations, I will first present a rather comprehensive view of classical speech act theory (part 2). After that, I will look upon a criticism of Austin and Searle close to my own (part 3 and 4). Finally, I will turn to my own theory (part 5).

2. Classical speech act theory

In classical speech act theory, it is argued that we can identify four or five basic illocutionary acts in accordance with the so-called performative analysis.

In How to Do Things with Words (1962) Austin presents the idea that engaging in language is to perform speech acts. According to the first version of his theory (lectures I-VII) we have two kinds of speech acts: constatives and performatives. While constatives are expressions identified by their capacity to be true or false according to facts, performative expressions have a different analysis: They are not related to pre-existing facts making them true or false; rather they create facts themselves by being correctly expressed according to conventions. Or to give an example: while the constative “It’s a sunny day” is true or false according to circumstances in the world, the performative “I promise to come” is not; rather, it creates the fact of being a promise. To say “I promise …” is eo ipso to make a promise.

Austin soon realized that he was on the wrong track. Closer analysis revealed both that constatives are performatives – “It’s a sunny day” is an act which can be performed correctly or incorrectly according to circumstances – and that performatives are, if not constatives in themselves, then at least closely connected to them – If I promise to come, then it must be true, both that I am able to come, and that you want me to come.

As a consequence, Austin altered his theory. In his new theory (lectures VIIIXII) he instead looked “[…] at the total speech act in the total speech situation.” (Austin 1962:147) and suggested that every speech act should be analyzed as composed of the following three elementary acts:

a locution – the uttering of some words with a definite meaning and a definite reference,

an illocution – the issuing of a certain assertion, order or promise with a definite (conventional) illocutionary force,

a perlocution – the bringing about a certain state in the mind of the hearer as a consequence of his understanding of the illocution.

As a major point, the performative analysis from Austin’s first theory has been preserved in his second theory, but in a more generalized form. Now, illocutionary acts in general – not just performatives – create new facts.

As Searle has pointed out (Searle 1968), Austin’s analysis is ambiguous. It is not clear whether “reference and meaning” is confined to the locution, “It’s a sunny day”, or whether it is including the expression of the illocution too, in cases where such expressions are used: “I am lucky to inform you that it’s a sunny day.” If the first is meant, we have the problem of explaining what an illocutionary act is when no linguistic means are used. If the second is meant, then we must include illocutions, contextually marked, along with illocutions expressed with explicit performative formulas like “I state that … “, “I promise that …” etc. or grammatical moods like indicative, imperative etc. as markers with a definite meaning and a definite reference, and reserve the term locution or the equivalent proposition(al act) for the propositional content that is the part prototypically expressed by a that-clause in phrases like “I state that …”, “I promise that …” Searle suggests the second alternative, especially since it also clears up the distinction between illocution and perlocution: while the purpose of illocutions (with their embedded locutions) are to get the hearer to understand the markers (words, contextual features etc.) expressing the illocution, perlocutions aims exclusively at instrumental success, namely the changing of the beliefs or actions of the hearer. Here perlocutions mentioned in the corresponding illocutions are of special interest, for instance getting the hearer to vote (perlocution) by urging him to vote (illocution) or convincing the hearer something about the weather (perlocution) by reporting something about it (illocution).

Connected with the question of the general structure of each speech act in language is the question of how many basic illocutions we have. This question Austin tries to answer in his last lecture in How to Do Things with Words. Here he introduces five classes. In A Taxonomy of Speech Acts (1975) Searle has made some major improvements on Austin’s attempt, so we will confine ourselves to Searles classification. As a prerequisite, Searle puts up a set of twelve parameters in order to control the classification. His three most important parameters are: illocutionary mode, direction of fit and mental mode. Solely based on these three parameters it is, according to Searle, possible to distinguish between four basic types of illocutionary acts, namely:

(1) assertives

(2) commissives

(3) directives

(4) expressives

A fifth class of illocutions, declarations, he later (Searle 1989) realized wasn’t a genuine class, but actually an ingredient in all types of social acts, including all speech acts. Searle’s taxonomy is generally recognized as an element in standard speech act theory. If we pair parameters with the four types of illocutionary acts, we get the following descriptions of the types:

(1) assertives have the illocutionary point of committing the speaker to the truth of the imbedded locution (proposition), they have a word to world direction of fit, and they express a wish from the speaker to let the hearer know the content of the imbedded locution,

(2) commissives have the illocutionary point of committing the speaker to a future act of his mentioned in the locution (proposition), they have a world to word direction of fit, and they express a wish from the hearer to get the result of the speaker’s future action realized,

(3) directives have the illocutionary point of getting the hearer to perform a future act mentioned in the locution (proposition), they have a world to word direction of fit, and they express a wish from the side of the speaker to get the result of the hearer’s future action realized,

(4) expressives have the illocutionary point of committing the speaker to the sincerity of the embedded locution (proposition), they have a world to word direction of fit, and they express a mental state of the speaker.

This amounts to Searle’s analysis of the assertive, the commissive, the directive and the expressive. As can be seen from the descriptions, the different values on the three parameters nicely separate the four types of illocutions from each other. Or so it seems.

3. A major problem in classical speech act analysis

It is easy to see that the classical theory makes the concept of meaning unnecessarily complicated: We have three kinds of conditions of satisfaction: truth for assertives, compliance for commissives and directives and sincerity for expressives.

This unfortunate multiplication of conditions of satisfaction means a violation of the truth functionality of language meaning: we can’t just combine illocutions aiming at truth with illocutions aiming at compliance and sincerity. This invalidates logic and ontology: instead of having a clear and simple first order predicate logic, building on assertions turning locutions true or false, we have to accept further illocutionary logics referring to entities of obscure ontological status: compliances and sincerities. It will be the aim of my considerations to show that we need not do that – that, actually, speech act theory only calls for assertions aiming at truth. To make my point, I first have to establish the critical context for my considerations.

4. How to establish an adequate analysis of the four basic classes of illocutionary acts?

Why is the classical analysis of speech acts problematic? Evidently, because speech acts according to this theory are not always giving us a truth value: admittedly, the assertive speech act “The door is closed” gives us a truth value; but neither does the commissive “I promise to come”, nor the directive “Shut the door!” Of course, you can ask what would be the case if the perlocutionary consequences came out true or false. But you cannot ask what the truth values of the locutions are. That is blocked by the performative analysis. According to this analysis, commissives and directives are giving us compliance values, and expressives sincerity values.

And that is a problem. Another problem is: expressions marking compliance and sincerity values as for instance “promise” have one meaning in “I promise to …” – aiming at compliance – and another meaning in “He promised to go” – aiming at truth.

Therefore, the question is: How can we get a better analysis of the commissive, the directive and the expressive?

Could we not, after all, just say that all locutions are always true or false? When I say “I’ll promise to come”, I do promise. And when I say “Please, go”, I do beg.

If we do that, we are, evidently, abandoning the performative analysis.

Then the expressions marking the illocutions just turn into simple assertions, namely assertions, not about what the embedded locutions are referring to, but about my promising or begging using these locutions. Then we have a situation where new things in the world, propositional attitudes, are just added to the things locutions are about.

But how shall we conceive of this non-performatory analysis of illocutions as just ordinary propositional attitudes?

A first try: Some have tried to apply the framework of possible worlds semantics. Accordingly, they have tried to characterize for instance an order parallel to the standard functional analysis of propositional attitudes like beliefs, wants and intentions: As John’s wanting a beer is a function from John to the set of possible worlds consistent with what John wants, so John’s promise to come is a function from John to the set of possible worlds consistent with what John wants the hearer to do.

This move in the analysis of illocutions is, I think, a bad move. To apply the framework of possible worlds semantics is, generally, to introduce entities of an unclear ontological status. For what is a set of possible worlds consistent with what John wants? Is it some distant place in an ideal world? Is it some place in John’s head? Or what?

To avoid this kind of meaning realism adhering to possible worlds semantics I suggest that we always stick to a constructivism located around a first order predicate logic as a theory of meaning, including a theory of meaning for propositional attitudes. I admit that it is difficult totally to renounce talk of possibilities. But we must insist on having criteria for our constructions in the actual world of publicly verifiable things. Otherwise, talk of possibilities is, in my opinion, empty talk.

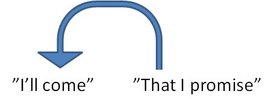

A second try: But if we cannot say that illocutions are functional expressions using the framework of possible worlds semantics, could we, then, just say that “I promise” and “I’ll come” amounts to two consecutive first order sentences where he first sentence is used to refer to the use of the second to state a fact? Here, maybe, the pronoun “that” could make the whole thing a bit easier:

Figure 1

Here the truth value of the assertion “I promise to come” is within reach in this world: “That I promise” is true if in fact I promise (to come); and “I’ll come” could be assigned a truth value if we can establish the situation where we can see the kept promise.

This try is more radical than the first. With this second try we have replaced the functional expression analysis with an analysis in terms of pronominal reference. This means that we have substituted the semantic analysis in the first try with a pragmatic analysis using exclusively first order predicate logic: The performative locution “I promise” is used to refer to a certain situation, described by the first order locution “I’ll come.” Here the two propositions must not be confused with a purely truth functional conjunction.

This second try is pretty close to a suggestion made by Donald Davidson (1979). For Davidson a speech act is at least paraphrasable as issued by two indicative sentences, one for the locution, A, and one – the mood-setter, as Davidson calls it – for the illocution, B – with the proviso that A can be, and normally is, used assertively without attaching any special mood-setter to it, since it is redundant to do it: “Indicatives we may as well leave alone, since we have found no intelligible use for an assertion sign.” (Davidson 1979:119). That is, by Davidson we first have a standard situation where we are using a sentence assertively without having any special indication, marker or mood-setter for the use of the sentence. Secondly, we have situations deviating from the standard situation where the speaker is using certain mood-setters – for instance a grammatical mood or an explicit performative – to indicate a mood: commissive, directive or expressive. The major point is that we consider the non-indicative moods to be a sort of explicit performatives. Therefore, we do not need any special performative analysis of the explicit performatives or any other markers of the illocutions. Every illocution has a common element, the locution, identical to its truth conditions. In this analysis Davidson just confirms the classical speech act theory.

Davidson’s suggestion is sketchy and vague, but I find it sufficiently promising to elaborate it further. Concerning the vagueness, it is not clear what Davidson hints at when he is talking about an assertive use without a mood-setter. Is he affirming the performative analysis of the assertive, or is he abandoning it? If the first is the case, he has to say more clearly that there is, after all, an indication of the assertive parallel to indicators of the other moods. If the second is the case, he must place assertions outside the reach of semantics – as purely instrumental acts (or otherwise quite obscure entities). Mood-setters for assertions are functioning semantically as sentences, indicating the assertions which are being made. But assertions without mood-setters – they cannot be conventions (Davidson 1979:113). But what are they then?

5. How to understand illocutionary acts: A third and final try

I think Davidson is on the right track in treating the mood-setter, the mark of the illocution, non-performatively, as a truth evaluable expression. But that does not make the performative analysis superfluous. As we have seen, Davidson is quite vague in his characterization of assertions without mood-setters. I want to remove this vagueness. To do that, I must establish four things: (1) carry out an analysis of Searle’s four speech act types, which shows that the non-assertive speech acts can, actually, be seen as assertives used in different instrumental settings; (2) establish an analysis of the mood-setters as a kind of assertions called Meta-assertives; (3) show how it is possible – and even needed – still to keep the performative analysis of the speech act on the stage.

As to (1) I will confine my analysis to directives and commissives.

Let us first look at directives. The question is: How do we spot a directive as a special sort of assertion? As a preliminary step, I first want to draw attention to the pertinent fact that all perlocutions are instrumental acts. That makes them equivalent to all corresponding non-linguistic instrumental acts: To order someone to mow your lawn amounts, instrumentally speaking, to the same thing as mowing your lawn yourself. But how can I order by using only assertives? It is actually quite easy. Let us stick to our example: here you are just asserting one or two facts about the situation or some of the consequences of acting reasonably in the situation – e.g. that the lawn is quite long haired these days, that it would be nice to have the grass cut or just “the grass is cut” (alluding to a situation stemming from some reasonable action). That will be sufficient to get the message across. In other words: To perform a directive speech act is just to make an assertion about some relevant facts about the situation or some future consequences of bits of reasonable instrumental action from the side of the hearer: In short: You make (perlocutionary) directives possible by making first order assertions about the world.

This explanation of the directive looks a little bit like a description of an indirect speech act the way it is explained by Searle (1975). And, of course, this much is true of the comparison that we need gricean maxims to get the message across, as Searle has demonstrated. But it is not quite an indirect speech act. In his concept of an indirect speech act Searle assumes that it is an indirect mean to perform an action which primarily could have been performed literally. This I am turning upside down: For me the perlocutionary form is the primary form of the directive. The illocutionary form – the form with an expression constituting that you are performing a directive speech act – is secondary to it. And it is easily explainable why this is so: It is always possible to refer to the repertoire of perlocutionary defined directives by using a meta-assertive: First, you are performing a ground floor assertive act pointing to an instrumental context, as for instance “The lawn is cut in five minutes.” Then you are performing a meta-assertive act concerning the instrumental context as a whole: “That’s an order.” This can, again, be shaped like an explicit performative – “I am hereby ordering you to ...” – or like an imperative. Or you can coin your own expressions for it if you want.

By introducing the meta-assertive, I have at the same time dealt with (2) above. This analysis is to a great extend the same as Davidson’s: First you have a ground floor assertion, and then you have a meta-assertion connected pragmatically to the first assertion. However, there are important differences. I will attend to that in the conclusion.

What about the commissives? How are they explained as assertives? Here the procedure is mainly the same as for directives. Both a commissive and a directive are directed at a future act, the directive at a future act of the hearer, a commissive at a future act of the speaker. The analysis of the commissive goes something like this: An assertive is always an obligation to speak the truth. But if that is so, a commissive can be seen as a special sort of assertion, namely an assertion about a future situation where the hearer can see, it is up to the speaker to secure the truth of the locution by bringing about the situation which will verify it. In short: You make a commissive by making an assertive about the world in the right instrumental context. Here again gricean means is necessary to get your message across, especially the maxim of relation. And meta-assertives can, of course, be established: “I promise” is a meta-assertive referring to the promise “I promise to come”.

Above, we left Davidson with an unsettled question concerning the assertive. We saw that he was not particularly clear about its role in cases without a mood-setter: was it realized by conventions demanding a performative analysis, or was it on the contrary an act falling totally outside the reach of semantics? Here the second alternative does not seem to be viable: If the assertive is totally outside the reach of semantics, it is a purely instrumental act. But such an act has not the power to constitute a locution bearing a truth value. To make an assertive illocution you must produce an expression with its own conditions of satisfaction – and that is for an assertive its own truth evaluating means. But that is what semantics is about. That leaves us with the first alternative, the performative interpretation: an assertive is not just to describe what is happening when you are asserting, it is not just truth conditional semantics. It is by the very wording to create a space for a locution having a certain truth value. The locution has a truth value. The locution is constituted by a truth conditional semantics. But not the assertion itself. The assertion is an illocution. It is a saying of something which counts as making an assertion, as Searle would have said. This leaves us with two problems.

The first problem is that we – as Davidson correctly points out – do not have any special use for an assertion sign – that is an expression, indicating that we are making this kind of act. But so what? That there is not an assertion sign is perhaps already a part of the solution: If the only illocutionary act is the assertion, then there is not any need for a special sign. What you say is just a hidden companion to the linguistic expression – the sentence – as a whole. The wording is – in general – the assertion.

The second problem is that we now have something not being totally analyzable in term of its truth conditions. Could that not bring us trouble with logic? It does not seem so: for disjunction, for instance, we, of course, must have that the assertion includes the disjunction as a whole: “ass(p) or ass(q)” is not, after all, the same as “ass(p or q)”. But that is not an obstacle for a truth evaluation of the locution. In contrast to a situation where we have several illocutions – a situation with unanalyzable commissives, unanalyzable directives and so forth as in the classical speech act theory – here we do not seem to have any problem for logic.

This leaves us – to sum up (1) – (4) above – with the following: a speech act is on the ground floor always an assertive illocution indicated as such by the very wording of it (confirming the performative analysis). It is – in itself – not a truth evaluable entity, but leaves us always with truth evaluable entities, namely locutions (standing under assertions). A speech act is always located in an instrumental context (partly) known by both speaker and hearer. This permits the use of Gricean means to make perlocutions including directives and commissives. Every speech act can be explicitly indicated by a locution in a meta-assertion. That goes for directives and commissives, and of course, also for assertives. That we sometimes need an explicit assertive is an indication of the general purpose of the meta-assertion in communication: The meta-assertive can function – and presumably actually functions – as the speaker’s instrument to indicate for the hearer which (instrumental) situation he should imply in circumstances where it isn’t obvious: Is it a pure assertive the speaker performs, or is it contextually embedded? This gives us a general pragmatic characterization of the meta-assertive: The meta-assertive functions generally as an elucidatory speech act.

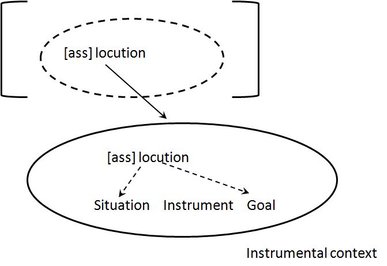

If we shall sum up, it is possible to depict all the results of our discussion in the following figure:

Figure 2

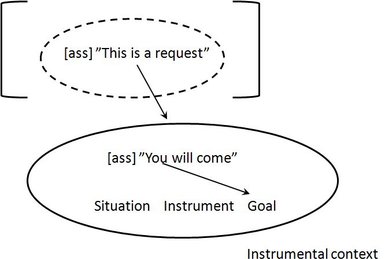

Here the parenthesis indicates that the meta-assertive in the broken oval is not necessary for carrying out the ground floor assertive. The ground floor assertive is here indicated as either referring to a situation (the broken arrow) – which makes it an assertive pure and simple – or a goal in the instrumental context (the dotted arrow) – which make it a commissive or directive perlocution. Figure 3 illustrates a directive speech act:

Figure 3

6. Conclusion

To conclude let me – to profile my own position – look upon the flaws in Davidson’s position. In Davidson’s analysis the ground floor assertive does not always give us a truth value. Apart from the assertive mood all the other moods only give us the intended truth conditions, not truth (or falsity). To refer to Davidson himself: “… there is an element common to the moods. Syntactically, it is the indicative core, which is transformed in the non-indicative moods. Semantically, it is the truth conditions of this indicative core. “ (Davidson 1979:121). By this truth conditional analysis of speech acts Davidson unfortunately commits himself to a same capital sin in speech act theory that has been committed since Austin and Searle, namely that of bringing all locutions under the same footing in relation to the various “illocutionary forces”: as bearers not of intended truth, but of intended truth conditions. Like many other speech act theorists, from Frege to Dummett, he knows of the privileged role of the assertive. But for all other illocutions he adheres to the same analysis as Austin, Searle and the rest: In performing an illocutionary act the speaker is directed at a locutionary content detached from its illocutionary heading with the result that truth is secondary to content: Speech is now a matter of fetching a locution from a standing stock of ready-made locutions. This underestimates the scope of the assertive. Whether truth is reached through already established meaning – making e.g. “This is a cat” a description – or it is first to be established in a word baptizing situation – making “That is a cat” a definition – is irrelevant to language. Assertion is the first thing. It is the indispensable instrument in situations of radical translation, deep down where language starts. And that is the place to start if we are going to have a correct picture of our capacity to build up language.

References

Austin, John L. (1962). How to Do Things with Words: The William James Lectures delivered at Harvard University in 1955. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Davidson, Donald (2001 (1979)). “Moods and Performance”. In Inquiries into Truth and Interpretation. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 109-122.

Searle, John R. (1968). “Austin on Locutionary and Illocutionary Acts”. The Philosophical Review 77, 4. 405-424.

Searle, John R. (1969). Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Searle, John R. (1979; 1. ed. 1975) “A Taxonomy of Illocutionary Acts”. In John R. Searle Expression and Meaning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 1-29.

(This Paper is printed in Hans Götzscche (ed.). Memory, Mind and Language: Hukommelse, psyke og sprog. Cambridge: Cambridge Scholars Press, 2010:

296-308.)